The FTSE 100 has become unloved and unwanted by an increasing number of investors.

I guess you can’t really blame them. After all, the FTSE 100 has grown from 6,900 in 1999 to 7,500 today, which is less than a 10% capital gain over 22 years.

By any reasonable stretch of the imagination, that’s a terrible return for an investment as volatile as the stock market.

To rub salt into this particular wound, US stocks have gained more than 200% over those same 22 years, as has the UK housing market.

And as you might expect, most investors today are keen to put more money into US stocks and UK property, precisely because they’ve performed so well over the last decade or two.

But are they right to do so, or should investors instead be shovelling at least some of their money into the relatively unloved UK stock market?

The bear case: The FTSE 100 is full of old-world stocks in decline

The narrative I hear most often is that the FTSE 100 is full of fossil fuel companies, tobacco stocks, mining companies and banks. These companies operate in industries that are in decline, are on the wrong side of the ESG movement or are in the process of being disrupted by new competitors or by regulation.

To some extent this is true. The ten largest stocks in the FTSE 100 includes Shell, BP, BHP, Rio Tinto, HSBC and British American Tobacco*, and it would be hard to argue that these can hold a candle to top US stocks like Facebook, Apple, Google and Microsoft.

To put it bluntly, the FTSE 100 is seriously lacking when it comes to glamorous tech stocks.

And given the banking crisis of 2009 and the commodity price collapse of 2014/15, the FTSE 100’s tilt to those sectors hasn’t done it any favours in recent years.

On that basis, so the argument goes, the FTSE 100 should be trading at its current low price and it should have a high dividend yield because future growth is likely to be almost non-existent.

That argument sounds reasonable, but I’m not so sure. After all, the FTSE 100 consists of 100 companies. Most of them aren’t banks or tobacco stocks or oil stocks, so most of them aren’t facing those structural headwinds.

So although the FTSE 100 does lack sexy tech stocks, I don’t think its prospects are likely to be as bad as the bear case suggests.

The bull case part 1: Optimism is a finite resource

In aggregate, US stocks and UK property have clearly outpaced UK stocks over the last 20 years. That is a simple fact.

It’s also a simple fact that most people look at past performance and almost nothing else when deciding where to invest.

If US stocks have gone up, that’s where they’ll invest. UK property doubles in five years? Great. Put all your savings into UK property. Bitcoin doubles in a day? Go all-in on Bitcoin.

This is called momentum investing and it’s driven by a naïve extrapolation of recent results combined with the fear of missing out on an investment that is (or seems to be) making all your friends rich.

But there’s a problem with this approach. The problem is that these periods of abnormally high returns are driven by optimism. Or more correctly, they’re driven by an increase in optimism.

That’s great, but optimism can only be increased so far.

At some point, you’re at maximum optimism. You’re fully invested in US stocks, UK property (or Bitcoin or whatever). You’ve borrowed to the hilt and pumped it all into your chosen investment.

And when everyone is fully invested, drinking Kool-Aid and singing “The Only Way Is Up”, then what?

You burn out, that’s what.

Optimism starts to fade. Imperceptibly at first. One day to the next. One week to the next. And as it starts to fade, prices start to fade. Ever so slightly, but enough to scare the flakiest investors out of the market.

Those investors are willing to sell at any price to escape the fear of further losses, so prices go down. Only very slightly, but enough to scare the next most jittery cohort of investors out of the market.

And on it goes, exponentially scaring more investors out of the market, because these investors were only in the market because prices were going up. But prices are now going down, regularly and with increasing speed, as more and more investors sell up and run for the exit.

Eventually, everyone is deeply pessimistic. Equities are dead (or at least, that’s what they said in the 1970s) and property carries an unacceptable risk of negative equity (or at least, that’s what they said in 1995 when I bought a four-bedroom flat in London for £40,000).

What does all this have to do with the FTSE 100? Nothing, directly. But it does have a lot to do with sky-high valuations in US stocks and UK property.

Those asset classes have done well, but their prices have increased far faster than their ability to generate sustainable cash (dividends or rent) and today, those prices are kept sky-high by pathological levels of optimism, near-zero interest rates and little else.

That does not bode well for US stocks or UK property over the next 20 years.

In contrast, the FTSE 100 hasn’t benefitted from (or suffered from) anything like that level of optimism.

The bull case part 2: Pessimism is also a finite resource

Since those heady days of 1999, when so many investors mistakenly thought we were about to step into a magnificent millennium of unbounded growth and joy, the FTSE 100 has quietly got on with the job of generating earnings and dividends for investors.

Those earnings and dividends have both more than doubled since 1999, so the idea that the FTSE 100 hasn’t grown in the last 22 years is simply wrong.

The FTSE 100 companies have more than doubled in size since 1999, in terms of profits and dividends. The only thing that hasn’t doubled is their price.

In the chart above, note the impact of the 2009 crash and the 2015 commodity price collapse on earnings, and the lack of impact on steady dividend growth (it took a global pandemic to temporarily halt dividend growth).

Historically, investors have been willing to buy the FTSE 100 for around 15 or 16-times the index’s ten-year average inflation-adjusted earnings. This is known as the FTSE 100’s CAPE ratio, or cyclically adjusted PE.

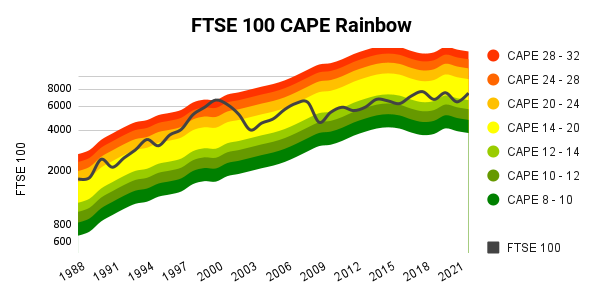

But in 1999, investors were manically optimistic. They thought the internet would enable companies to grow fantastically quickly for decades to come, so they were willing to buy the FTSE 100 at a much higher price-earnings ratio than the historical norm. In fact, the FTSE 100’s CAPE ratio peaked at 32 in 1999, more than double the long-term average.

Of course, we now know that investors were wrong to be so optimistic and most companies didn’t grow fabulously quickly for decades. In fact, the world muddled along pretty much as it had for the previous century, with overall growth in the mid-single-digit range.

Over those 22 years from 1999 until today, the FTSE 100’s CAPE ratio has wobbled around erratically, driven up and down by optimism and pessimism.

Today, investors are relatively pessimistic about the FTSE 100’s future. They look back and see 22 years of zero capital gains and an index full of boring old companies that no teenager worth their salt would invest in.

At 7,500, the FTSE 100 has a CAPE ratio which is a positively mediocre 16, almost exactly equal to its long-run average.

So the FTSE 100’s CAPE ratio has halved since 1999 while its earnings have doubled. The net result is that the index hasn’t moved in 22 years, and that’s all that most investors will focus on.

Note that green in the chart above is cheap, yellow is fair value and red is expensive.

But if that’s all they focus on, then they’ll be missing the most important point, which is that over the next 20 years, the FTSE 100 is extremely unlikely to produce results anything like as bad as the last 20 years.

If we assume, quite reasonably, that the FTSE 100 can again double its earnings and dividends over the next 20 years, then there is almost no chance that its CAPE ratio will halve again to offset those gains.

If CAPE halved again it would be at 8, and it only gets that low when the entire economic system is either on the brink of collapse or has actually collapsed.

A more reasonable assumption is that the FTSE 100’s CAPE ratio will be close to its average value 20 years from now. And if that happens, the FTSE 100’s price will have doubled, assuming that’s what its earnings and dividends do.

And of course, given the relatively low starting valuation, the FTSE 100 also have a relatively attractive dividend yield.

Those dividends are currently depressed because of the pandemic, but as and when they return to 2019 levels (probably sooner rather than later I would think) the FTSE 100’s dividend yield, with the index at 7,500, would be 4.4%.

The total return from that 4.4% yield, plus the reasonable prospects for a doubling of dividends and capital within 20 years, is, in my opinion, likely to be better than the total return from either US stocks or UK property over those same 20 years.

* At the time of writing I owned shares in British American Tobacco and it was a holding in the UK Dividend Stocks Model Portfolio.

Leave a comment