Although the decades-old currency pegs of the Gulf Arab region often come under strain in depressed oil markets, they always have survived. This time, however, energy prices are at historic lows and the coronavirus outbreak has unleashed recessions that are squeezing government budgets like never before. With some of the Gulf currencies under pressure from speculators, are the pegs facing their sternest test?

1. How are the gulf dollar pegs under pressure?

As Saudi Arabia embarked on an oil-price war in March by boosting crude production, traders were betting through the derivatives market that the region’s currencies would weaken within a year. Such a scenario is possible only if countries abandon their currency pegs. Fixed exchange-rate regimes in Asia were swept away during the currency crisis of the late 1990s, when speculators forced the likes of Thailand and South Korea to abandon their links with the dollar. Currency pegs are now largely confined to the major oil producers in the Middle East which appear unwilling to let them go.

2. Who has pegs and why?

The six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council — Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — have been running currency pegs or managed foreign-exchange regimes since the early 1970s. Kuwait pegs the dinar to a basket of currencies believed to be dominated by the U.S. dollar, while the others are linked solely to the greenback. With oil and gas priced in dollars, the pegs have helped shield the countries from the volatility of energy markets and allowed central banks to accumulate foreign-currency reserves in the good times. Indeed, the robustness of pegs relates in large part to the size of countries’ foreign-exchange reserves and foreign assets held by their sovereign wealth funds.

3. Why the concern now?

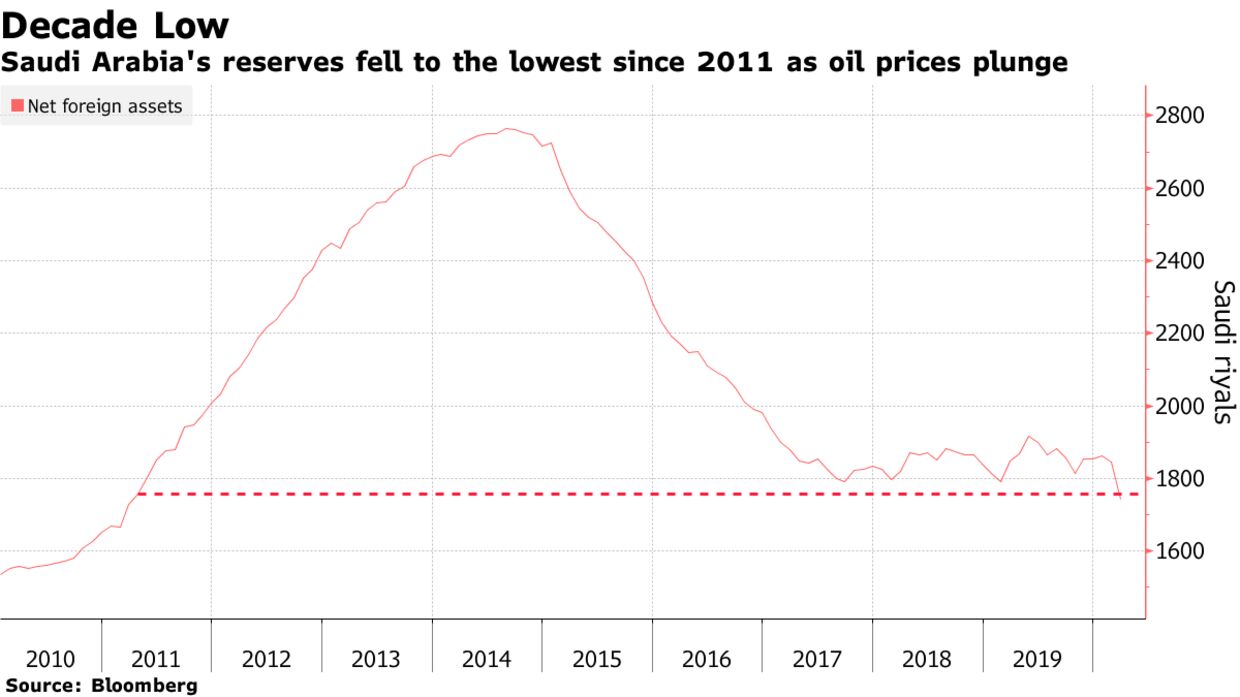

Most of the Gulf countries remain heavily reliant on hydrocarbons to pay the bills — Saudi Arabia gets around two-thirds of its revenue from oil and Kuwait about 90% — so the slump in prices has put the region’s economies under huge stress. As the price of Brent crude crashed by more than half in March, Saudi Arabia, the largest oil exporter, depleted the central bank’s foreign-exchange reserves by $27 billion that month, a decline of more than 5%.

4. Have we been here before?

The system has survived stern tests, including successive years of low oil prices in the 1990s, a period of dollar weakness before the financial crisis in 2008 and another oil-price crash in 2014. Speculators jumped in then to challenge the Saudi peg, with 12-month forwards — which investors use to bet on the peg breaking or to hedge in case it does — climbing to an all-time high of 3.85 per dollar in 2016. (The peg is 3.75.) Instead of choosing to devalue the riyal, the kingdom cut spending and subsidies and turned to debt markets to fund its budget deficit. Its neighbors have adopted similar strategies.

5. How have those strategies fared?

Progress in diversifying revenue away from oil has been mixed as have attempts to rein in spending. Government debt as a share of gross domestic product has jumped across the region since 2014. Saudi Arabia will run its seventh consecutive budget shortfall this year and the U.A.E. is on course for a record deficit, the International Monetary Fund estimates. It all points to the need for drastic economic measures to combat the twin punch of low oil prices and global recession. The Saudis in May announced a trebling of VAT and lowered state allowances.

6. Which pegs appear most vulnerable to speculators?

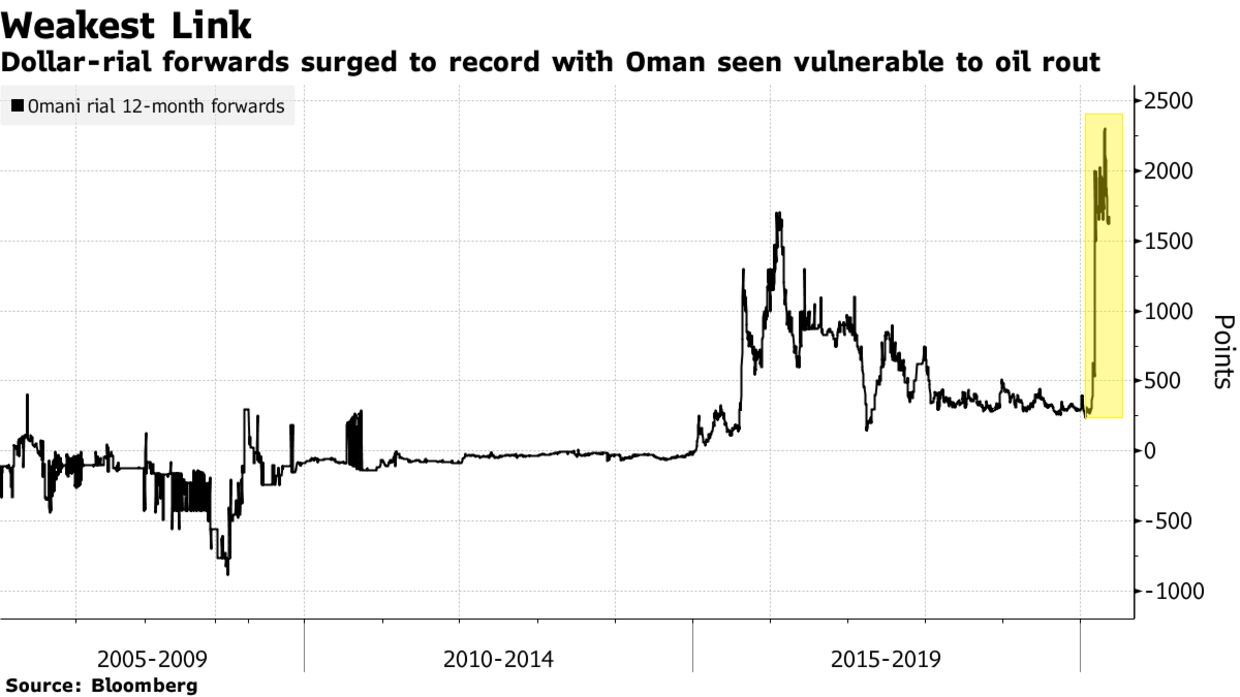

Saudi Arabia, the U.A.E., Kuwait and Qatar all have the firepower in the form of sizable currency reserves to defend their pegs. The Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority said in May its foreign-exchange reserves cover 43 months of imports, as it reaffirmed its commitment to maintaining the peg. The most vulnerable appear to be Oman and Bahrain, given their precarious public finances and strained reserves. Bahrain requires an oil price of $95.6 a barrel to balance its budget, while Oman needs $86.8, the highest in the GCC, according to the IMF. Bahrain at least has the cushion of a $10 billion bailout package from its wealthier neighbors.

7. So Oman is the weak link?

Possibly. It lacks a backstop credit line from its regional allies and may also pay the political price of having resisted taking sides in regional disputes or supporting Saudi Arabia’s foreign policies. As the largest non-OPEC oil producer in the Middle East, Oman faces a seventh straight year of budget deficit, with this year’s set to widen to 17.5% of GDP from 9.7% in 2019, according to S&P Global Ratings. In its favor? The fear of a domino effect should the first peg in the region go. S&P said it expects other GCC nations to come to Oman’s rescue should significant external liquidity pressures threaten its peg because any contagion effect could hurt the region.

8. What’s so bad about a broken peg?

As well as spurring speculators to challenge other pegs, any devaluation would raise the risk of inflation taking grip through higher import costs, reducing people’s purchasing power and eroding real incomes. It would also lower the value of local savings and may prompt capital outflows as citizens move their money overseas to safeguard its value. Given that dollar-priced oil and gas remain the dominant exports, the region’s economies would be unlikely to gain much from weaker currencies. Options for countries post-peg include moving to a managed floating exchange rate or — for those tied to the dollar — to a peg against a basket of multiple currencies, as Kuwait did in 2007.

Leave a comment